Ophelia

Trivia:

Millais sold Ophelia to Henry Farrer for 300 guineas in 1851 before Millais had completed it.

A mezzotint engraving of Millais’s Ophelia by James Stephenson was published by Henry Graves in 1866.

Documentation:

Malcolm Warner notes the significance of flower symbolism in Millais’s Ophelia :

“[Ophelia] contains dozens of different plants and flowers painted with the most painstaking botanical fidelity and in some chases charged with symbolic significance. the willow, the nettle growing amogst its branches and the daisies near Ophelia’s right hand, associated respectively with forsaken love, pain and innocence, are taken from Shakespeare’s text. The purple loosestrife in the upper right corner is probably intended for the ‘long purples’ in the text…The pansies…floating on the dress…may come from the scene shortly before Ophelia’s death…where she mentions pansies among the flowers she has gathered in the fields. The pansy can signify both ‘thought’ and ‘love in vain’. In the same scene she speaks of violets that ‘withered all when my father died’, an image that draws on the association of violets with faithfulness – although they can also symbolize chastity and the death of the young. Millais undoubtedly had one or more of these meanings in mind when he gave Ophelia a chain of violets around her nect. The roses near her cheek and at the edge of her dress,,,,, and the field rose on the bank, may allude to her brother Laertes’ calling her ‘rose of May’…The rest of the plans and flowers are Millais’ rather than Shakespeare’s. The poppy next to the daisies is a symbol of death and the faded meadowsweet on the bank to the left of the purple loosestrife can signify ‘uselessness’: the pheasant’s eye near the pansies and the fritillary floating between the dress and the water’s edge are both associated with sorrow; and the forget-me-nots at the mid-right and lower left edges…carry their meaning in their name….daffodils can mean ‘delusive hope’, which would certainly have made them appropriate for this subject.”

Malcolm Warner, “John Everett Millais, Ophelia” in Leslie Parris, ed., The Pre-Raphaelites. (London: Tate Gallery Publications, 1984), 97.

Michelle Facos situates Millais’s Ophelia in the context of nineteenth-century psychology debates:

“The unstated lesson of Ophelia’s tragedy was that a woman’s fate is determined by the men in her life. Without male guidance or a male object of devotion, Ophelia was lost and helpless. That female independence could precipitate insanity was supported by ‘scientific’ research….The research of Jean-Martin Charcot – father of psychopathology and teacher of Freud – into the female ‘malade’ of hysteron-epilepsy, conducted during the 1870s, supported the myth of inherent female irrationality, especially among young, unmarried women….To citizens of the late nineteenth century, Ophelia represented the fate of single women driven over the brink by circumstances that men would normally overcome and epitomized an erroneous, if widely accepted, link between gender and insanity.”

Michelle Facos, Symbolist Art in Context (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 123-4.

Kimberly Rhodes notes:

“When John Everett Millais exhibited Ophelia at the Royal Academy in 1852 he challenged conventional notions of Ophelia’s characterization and Shakespearean illustration. In choosing Pre-Raphaelite style and an unorthodox narrative moment (off stage suicide), he offered an image of Ophelia that resonated beyond its historical moment, but is favored by popular audiences today. Other mid-Victorian artists who represented this scene from Hamlet, such as Richard Redgrave and Arthur Hughes, usually depicted Ophelia poised on a willow branch that arches over a brook just before she falls (or jumps) to her death, assuming the audience’s knowledge of her imminent demise and appealing to their taste for pathos….

By veiling the emotional significance of Ophelia’s death with a profuse veneer of detail, Millais privileged surface effect over content and divested the literary heroine of her traditional emotive impact in favor of a sensationalistic style. Millais thus created a crisis of sorts in literary illustration that allowed the painter power to skew conventional readings of female characters like Ophelia from one indicative of virtue to one of transgression, perversity, and decadence. The irony is that Millais did this by being quite literal in his depiction of Ophelia’s death, rendering the entire text rather than a portion of it. Traversing Shakespeare’s text from beginning to end, one finds Millais adhering strictly to his source: a willow branch arches over the brook and Ophelia’s head; flowers of the type mentioned in Gertrude’s monologue either grow on the bank or float in the water; her white embroidered and beaded dress spreads into a bell as she sinks; and her mouth is agape to indicate singing.”

Kimberly Rhodes, Ophelia and Victorian Visual Culture: Representing Body Politics in the Nineteenth Century (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1988), 87, 90.

Similar Subjects by Other Artists:

Henry Singleton, Ophelia, 1791 Royal Academy exhibition

Benjamin West, Ophelia Before the King and Queen, 1792 (Cincinnati Art Museum)

Richard Redgrave, Ophelia Weaving Her Garlands, 1842 Royal Academy exhibition (Victoria & Albert Museum, London)

Auguste Préault, Ophelia, 1842 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris)

Arthur Hughes, Ophelia, 1852 RA (Manchester City Art Gallery, UK)

Eugène Delacroix, The Death of Ophelia, 1853 (Louvre, Paris)

Web Resources:

About the Artist

Died: London, 13 August 1896

Nationality: English

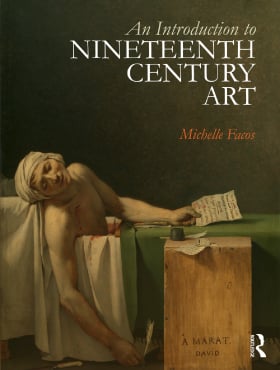

Buy the Book

Buy the Book