About the Artist

Anne-Louis Girodet (de Roussy-Trioson)

Born: Montargis, 29 January 1767

Died: Paris, 9 December 1824

Nationality: French

Collection

Chateaux de Versailles

Documentation

Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby discusses the issue of race in Girodet’s Monsieur Belley :

“Girodet, I am arguing, was intensely cognizant of the distance between himself and his model. His portrait produces Belley for us, brings him close, but also sets him apart as a being that cannot be confused with oneself. This is the difference of the physically non-identical; the portrait offers neither the fantasy of interpenetrating boundaries nor the fantasy of psychic habitation. Images of the suffering black body asked for the viewer’s empathetic identification. The portrait of Belley does not demand such an act of projection; indeed it thwarts it. A hostile interpretation of the portrait would describe it as an objectification, but what interests me is the way the picture’s emphatic empiricism enhances our sense of the personal autonomy and psychological independence of a specific black man precisely because it insists, with extraordinary intensity and detail, upon his irreducible distinctness. Opacity wedded to particularity can add up to respect for human beings’ fundamental incommensurability.

Fundamental incommensurability? To valorize individual autonomy is to rehearse an elite prerogative. Bring biological conceptions of race into view and see how ‘incommensurability’ or ‘difference’ become slurs. In Revolutionary France, the very terms of autonomous selfhood were insidiously inflected when black bodies were at issue. Does not incommensurable difference, after all, precisely recapitulate the thesis of separate races?

It is important to recall that the utopianism of radical equality had precipitated its equally extreme renunciation. Indeed, Revolutionary Paris witnessed an explosion of racial insults in public discourse. “

Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, Extremities: Painting Empire in Post-Revolutionary France (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 49.

Mary L. Bellhouse addresses the issue of sexuality in Girodet’s Monsieur Belley :

“According to psychoanalytic theory, the male is necessarily threatened with feeling inadequate in relation to other men, because the production of the masculine rests on comparison with an unknown foreclosed imago. It is for this reason that the structure of hierarchy has such a deep purchase on male subjectivity. But the Belley portrait with its violation of classical canons threatens the male spectator who may confront a gap between the size of his own genitalia and what is shown in the painting. Whatever Girodet’s intentions, the Belley portrait puts into circulation in the public sphere in France an early version of the charged claim that black men have unusually large genitals.”

Mary L. Bellhouse, “Candide Shoots the Monkey Lovers: Representing Black Men in Eighteenth-Century French Visual Culture,” Political Theory, vol. 34, no. 6 (December 2006): 767.

Sylvain Bellenger comments on skin color in Girodet’s Monsieur Belley :

“Far from being a militant work with the clear and limpid message of a flag or slogan, Portrait of Belley exists as a fabric of ambiguities. And this should not surprise us, since Girodet liked to plunge all his subjects into sensual depths that are charged with the evocative power and polysemy appropriate to poetry....

The nuanced complexity of his color is also taken up, as a sort of banner advertising the artist’s technical expertise, in the enormous dark marble pedestal that occupies nearly a quarter of the composition…In the end, it is unimportant if the subtlety of the marble is real or invented. Whether real or painted faux marble, the material accentuates the pure visuality of the painting and introduces a dialectic with the subject….

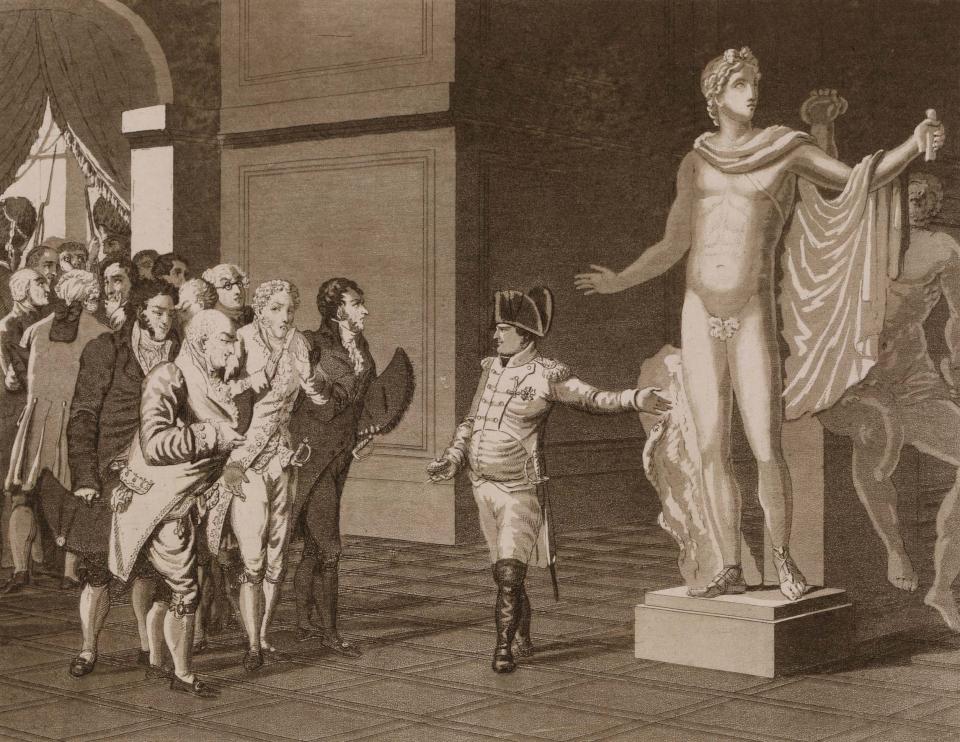

Veined like the hands of Belley, the marble pedestal contains echoes of the tones of the deputy’s skin. Girodet also chose to represent white skin through marble – this time white Carrara marble for Raynal’s bust. Similar to the subtle rendering of Belley’s skin, the bust is not pure white, but instead has reflections of clear brown, ivory, sepia, and gray. This question of the skin and its color, so essential to painting the body, has recently been posed by Jean Clair: ‘What color is the skin? This simple question has never ceased to concern me, ever since I was a child…Clothes were easy – blue, green, yellow-red, black, or gray…but the skin? …skin was not white. It was not pink., Neither yellow, nor mauve or violet, nor brown. A little of all this certainly.’…On the artist’s palette, racial identification is thus effaced, as if the Manichean questions of black and white would lead art and morality toward a dead end. Racial characterization resists chromatic categories in the same way it resists ethnographic categories. Girodet humorously highlighted this impossibility of categorization, when he discussed it within the realm of the sancrosanct concept of the beau ideal. In a delivery made before the academies of the Institut de France at their annual public meeting, he offered the following speculation: ‘All the peoples of Europe represent the Devil with a black skin, whereas the Ethiopians give to their evil demons a white face; one can thus assume that in the eyes of a native Abyssinian or Kalmuck Tartar, the more strangely original figure – I almost said the most ridiculous, indeed the most frightful figure – would be, for example, that of the great Apollo Belvedere.’”

Sylvain Bellenger, “Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen,” in Sylvain Bellenger, ed., Girodet 1767-1824 (Paris: Musée du Louvre, 2005), 333.