Symphony in White No. 1: The White Girl

Documentation:

Contemporary critic Paul Mantz visited the Salon des Refusés and found Whistler’s painting consistent with tradition rather than an attack on it:

“[O]ne would have to be ignorant of the history of painting to dare claim that Mr. Whistler is an eccentric when, on the contrary, he has precedents and a tradition which should not be disregarded, particularly in France…I do not know if Mr. Whistler has read the life of Oudry as told by the Abbé Gougenot but, had he done so, he would have learned that this skillful aster frequently practiced grouping ‘objects of different whites’ together, and that, in the Salon of 1753, he exhibited among others a fairly large picture ‘representing various white objects on a white background, namely: a white duck, a damask table napkin, some porcelain a cream pudding, a candle, a silver candlestick and some paper.’ These associations of similar shades were understood by everyone a hundred years ago, and the difficulty of painting them, which today would nonplus more than one master, passed for child’s-play at that time: in seeking such an effect, Mr. Whistler is thus continuing the French tradition, and that was no reason for rejecting his picture….the truth is that Mr. Whistler’s work works a strange charm: in our view, the Woman in White is the principal piece in the heretics’ Salon.”

Paul Mantz, “Salon of 1863,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts (July 1863), np. In Robin Spencer, ed., Whistler. A Retrospective (New York: Hugh Lauter Levin, 1989), 71.

In an 1862 letter to George Lucas, Whistler speculated on reasons for, and the significance of, the rejection of The White Girl from the Royal Academy exhibition:

“Now then for my news - though I take it, you have heard it already through Fantin [Henri Fantin-Latour] - 'The White Girl' was refused at the Academy, where they only hung the Brittany sea-piece and the Thames Ice sketch. Both of which they have stuck in as bad a place as possible - Nothing daunted I am now exhibiting the White Child at another exposition where she shows herself proudly to all London - that is to all London who goes to see her! She looks grandly in her frame and creates an excitement in the Artistic World here which the Academy did not prevent or forsee - after turning it out I mean. In the catalogue of this exhibition it is marked 'Rejected at the Academy' What do you say to that? Isn't that the way to fight 'em! - Besides which it is affiched all over the town as:

‘Whistler's Extraordinary Picture The Woman in White !’

That is done of course by the Directors but certainly it is waging an open war with the Academy - Eh?”

Quoted in Robin Spencer, “Whistler’s ‘The White Girl’: Painting, Poetry and Meaning,” The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 140, No. 1142 (May 1998): 304.

Most early reviews of The White Girl were negative, including this anonymous review in a July 1862 issue of the Athenaeum :

“It is one of the most incomplete paintings we ever met with. A woman, in a quaint morning dress of white, with her hair about her shoulders stands alone, in a background of nothing in particular… The face is well done, but it is not that of Mr Wilkie Collins’s Woman in White.”

While Whistler didn’t object to the mistitling or misreading of The White Girl for commercial purposes, he did object when such misunderstandings led to a bad review. He responded to the above review in a 5 July 1862 letter to the Athenaeum :

“May I beg to correct an erroneous impression likely to be confirmed by a paragraph in your last number? The Proprietors of the Berners Street Gallery have, without my sanction, called my picture 'The Woman in White'. I had no intention whatsoever of illustrating Mr. Wilkie Collins's novel; it so happens, indeed, that I have never read it. My painting simply represents a girl dressed in white standing in front of a white curtain.”

Quoted in: Elizabeth R. and Joseph Pennell. The Life of James McNeill Whistler (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1911), 69.

Whistler explained his artistic philosophy and his reason for including musical terms in his works’ titles in his famous “Ten O’Clock Lecture,” a part of which was published in his book The Gentle Art of Making Enemies :

“Why should not I call my works ‘symphonies,’ ‘arrangements,’ ‘harmonies,’ and ‘nocturnes’? I know that many good people think my nomenclature funny and myself ‘eccentric’… The vast majority of English folk cannot and will not consider a picture as a picture, apart from any story which it may be supposed to tell…

As music is the poetry of sound, so is painting the poetry of sight, and the subject-matter has nothing to do with harmony of sound or of colour [sic]… Art should be independent of all clap-trap – should stand alone, and appeal to the artistic sense of eye or ear, without confounding this with emotions entirely foreign to it, as devotion, pity, love, patriotism, and the like. All these have no kind of concern with it and that is why I insist on calling my works ‘arrangements’ and ‘harmories…”

James McNeill Whistler, “The Red Rag,” in The Gentle Art of Making Enemies (London: William Heinemann, 1890), 126-7.

Robin Spencer speculates on the reason why Whistler’s White Girl was rejected from the 1862 Royal Academy exhibition:

[Art historian] “David Park Curry is surely right to see sexuality in The White Girl, and to contrast the symbolic purity of white with the animal presence implied by the bear skin rug. While unidentifiable with specific fallen women, real or fictional, Whistler’s representation of a young woman dominating an animal parodies Edwin Landseer’s The Shrew Tamed (now lost), which depicted a thoroughbred horse on straw, with a young woman dressed in riding habit lying next to it. Exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1861, a year beforeThe White Girl was submitted, Landseer’s The Shrew Tamed became a sensation after the model was shown to be the successful courtesan Catherine Walters (known as ‘Skittles’); it provoked ‘responses which ranged from outright condemnation to hesitant admiration.’ The critical responses cited by [art historian’ Lynda Nead demonstrate how Landseer’s image revealed ‘the kinds of relationships which may be established between meaning and definitions of moral and artistic propriety.’ Perceiving the reversal of traditional power relations and gender, The Times critic wrote of The Shrew Tamed : ‘The lady reclines against [the horse’s] glossy side, smiling in the consciousness of female supremacy, and playfully patting the jaw that could tear her into tatters, with the back of her small hand. For horses read husbands, and the picture is a provocation to rebellion addressed to the whole sex.’

I am not suggesting that Whistler consciously substituted a deflowered virgin for a courtesan, or a dead animal for the dangerous live one of Landseer’s image; he would not have risked the Academy’s censure by invoking its memory. But the ambiguous conjunction of girl and animal in The White Girl is strongly suggestive of the discourse documented by Nead, and of the nature and conflicting identity of female sexuality which exercised Victorian society. …four members of the 1862 committee had also served in 1861 and would have been mindful that the exhibition of so prominent and sexually ambiguous an image as The White Girl might run the risk of attracting the same kind of unwelcome publicity which Landseer ’s picture had drawn the previous year.”

Robin Spencer, “The White Girl : Painting, Poetry and Meaning,” The Burlington Magazine, vol. 140, no. 1142 (May 1998): 310.

Michael Fried discusses the psychological state portrayed in Whistler’s White Girl and contemporary attitudes toward viewing works of art:

“But the most telling commentary for my purposes is by [Horace de] Viel-Castel who after comparing Whistler’s figure to the sleepwalking Lady Macbeth went on to discuss what he took to be the wolf’s pelt on which she stands (it’snow thought to be a bearskin), focusing in the end on the animal’s head, ‘stuffed and furnished with enamel eyes, [which] thrusts menacingly toward the beholder’. In other words, Viel-Castel found in Whistler’s canvas both an absorptive, beholder-denying structure (keyed to the woman’s state of mind) and a facing, beholder-agressing one (based on the orientation of the animal pelt…I don’t quite wish to say that Viel-Castel’s description captures Whistler’s intentions in the Woman in White or even, putting the question of intentions aside, that it accurately records the painting’s appearance…the response to the Woman in White makes it plain that there existed in the first half of the 1860s a highly structured discursive field oriented to the issues of absorption and beholding within which the Woman in White…was bound to be seen, described, and judged – and, before all these, within which it was painted…[W]hat may seem a lack of perfect accord between the critical commentary on the Woman in White and the painting itself is in fact the sign of a meaningful relation between the two.”

Michael Fried, Manet’s Modernism or, The Face of Painting in the 1860s (Chicago-London: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 223-4.

Similar Subjects by Other Artists:

Charles Chaplin, Girl in White Dress, ca. 1860 (The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore)

Geirge Dunlop Leslie, Celia's Arbor, c. 1868 (Kunsthalle, Hamburg)

Web Resources:

smarthistory: Whistler, Symphony in White No. 1: the White Girl

About the Artist

Died: London, 17 July 1903

Nationality: American

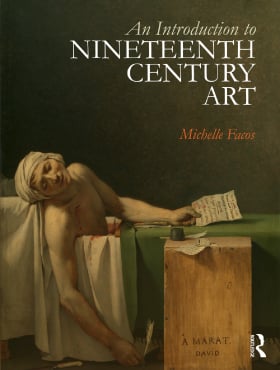

Buy the Book

Buy the Book