Battle of Eylau

Documentation:

David O’Brien sheds light on the several purposes served by Gros’s Battle of Eylau :

“What benefit for the government lay in Gros’s terrible exploration of suffering and death? Why, for example, depict so explicitly the blood frozen onto the blade of the bayonet in the center foreground, or the effect of the freezing weather on the skin of the lager-than-life corpses, or the pool of blood seeping from the head of the fallen Frenchman? What are we to make of the thrown-back head of a Russian corpse place on the same vertical axis occupied by Napoleon, inverting the face of the conqueror, healer, and peacemaker with his own pathetic countenance? Answering these questions will entail a consideration of the government’s desire to use art as propaganda while preserving the illusion that artists were responding directly to popular public sentiments. The painting allowed viewers considerable latitude to explore some of the most disturbing aspects of the subject. It spoke to rumors and a new understanding of war circulating in the public sphere and reconciled this knowledge with the official version of events. Rather than offering an unequivocal, obviously propagandistic interpretation of events, the painting invited viewers, in a limited way, to exercise their own judgment, thereby enacting the ostensible freedom and autonomy characteristic of the ‘Republic of Letters.’

In the course of the eighteenth century, art was increasingly identified with the ‘Republic of Letters’ (or, alternatively, the ‘Republic of Taste’ or the ‘Republic of the Arts’), a polity in which individuals freely exchanged ideas and where public opinion was a powerful judge of artistic success and failure. Pierre Bayle, an early and seminal formulator of this imaginary community, offered the following definition in 1692: ‘The Republic of Letters is an extremely free state. One recognizes there only the rule of liberty and reason, and under their auspices one wages war innocently against whomever it might be….Everyone there together is sovereign, and liable to everybody.’”

David O’Brien, “Propaganda and the Republic of the Arts in Antoine-Jean Gros’s Napoleon Visiting the Battlefield of Eylau the Morning after the Battle,” French Historical Studies, vol. 26, n. 2 (Spring 2003): 282-4.

John McCoubrey points out references to ancient Rome in Gros’s Battle of Eylau :

“It may have been, however, that Gros…turned to the art of Rome and found there not only appropriate representations of imperial warfare but also a solution to his pictorial problem and a justification for the crowded, flat painting which bothered his critics. Indeed the change toward the densely packed, relief-like space of his final painting, as well as the gestures and disposition of figures…suggest that he had been studying Antonine battle sarcophagi. His arrangement of figures is particularly close to the famous Sarcophagus Ludovisi, which had been well known since the seventeenth century. In this relief, figures jam the whole field, each making its own space and pressing out toward the edges. The unknown general, like Napoleon, rides at the top, separated from those around him less by his position than by his gesture and his calm, almost detached attitude. Below him fallen barbarians look up imploringly, and at the base lies one of their dead with upturned head like the fallen Russian at Eylau.

Given the scene of imperial grandeur, the problems of the program and the compositional changes introduced in his final painting of Eylau, it seems likely that Gros may have also had in mind the most prominent Roman imperial sculpture, the reliefs of Trajan’s Column. They were much in the minds of the new masters [the French] of Rome. One general even suggested that the column be dismantled and set up in Paris, and Parisians did see its imitation, the Colonne d’Austerlitz, rise in the Place Vendôme. Even without this new publicity any student of art might have gone to the Trajanic reliefs, as artists had traditionally done, for instruction and inspiration. In addition to the monument itself and Bartoli’s [engraved] plates, there had been casts available to French students in Rome and Paris since 1670, and during the First Empire there had been a project to decorate the Cour Carée [room in the Louvre] with them. David had studied them avidly as a student…For the military subject and imperial drama Gros was called upon to represent there was no more suitable model….

In Gros’ Eylau, as elsewhere in Napoleonic art, a conscious parallel between Trajan and Napoleon was undoubtedly intended. We know that the analogy to Roman campaigns on the frontier was not lost upon the latter who, in a bulletin issued just after Eylau, scornfully termed his enemies ‘Russians, Kalmuks, Cossaks, those people of the North who once invaded the Roman Empire.’”

John Walker McCoubrey, “Gros' Battle of Eylau and Roman Imperial Art,“ The Art Bulletin, vol. 43, n. 2 (June 1961): 137-8.

Similar Subjects by Other Artists:

Benjamin West, The Battle of the Boyne, 1778 (Mount Stewart, Newtownards, Northern Ireland)

About the Artist

Died: Paris, 25 June 1835

Nationality: French

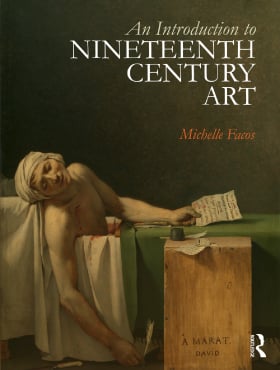

Buy the Book

Buy the Book