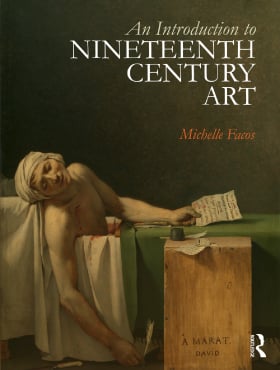

Marat

Documentation:

The mid-nineteenth-century political activist and art critic Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809-65) offered his opinion of David’s Marat :

“The expiring Marat is a light in the storm of Revolution. I don't know what kind of criticism one could have of this painting; perhaps it is just a depiction of a reality that he witnessed one hour after the event. This setting conveys a better understanding of the unfortunate message of the artist's idea. When I think of Marat, friend of the common man, I too disregard his enemies and don't concern myself with such details either. The truth that remains, and that of which I am in awe, is that this corpse will become the symbol of the Terror, that everything seems to have been put together by an infernal genius in order to excite pity and anger, and to give the plotters and criminals of the Revolution a context for their conspiracies. This popular journalist lives in a cave, his exhausted body in the service of the sans culottes in a poor lodging with cold walls, a frail man who's been assassinated in the bath where he ceaselessly works. He has just corrected his last writing. This sad vengeance of a vulnerable person by the hand of an elegant aristocrat, finally, this Marat who was a monster yesterday is today a martyr, a saint. That's what art could not have invented and what comes spontaneously from the palette of David; the political insanity of a woman....Seventeenth-century Dutch painting, which produced more accomplished works, never produced anything this powerful."

Pierre-Joseph Prudhon, Du Principe de l’art et de sa destination sociale (Paris: Garnier Frères, 1865), 120-1.

Jörg Traeger argues for the path-breaking status of David’s Marat :

“…David’s Marat is not a reportage, but a political interpretation of the attack. instead of actual events, the picture introduces new elements in all decisive aspects. Each of these elements is ambiguous from an iconographical viewpoint. The Christian aspect is complemented by the pagan element, the sacred by the profane. The two aspects cannot be separated from one another, but are intricately entwined. The image of the dying republican is one and indivisible from the republic itself, for which he has sacrificed himself. Marat is the man of Nature, and thus the man of a new era of universal history. The fundamental ethical category of this man is called ‘bienveillance’; the corresponding religious system is that of ‘civic religion’. The creed of this new religion is the articles of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. Supreme divinity is now the Supreme Being. The ‘man’ and the ‘citizen’ attain immortality through the republican martyr.”

Jörg Traeger, "Marat: La Religion Civile,“ David contre David, 2 vols., Régis Michel, ed. (Paris: La Documentation française, 1993), 414.

Writing half a century after David painted Marat and at a time when revolution in France was again beginning to brew, the French poet and critic Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) considered this painting David’s masterpiece:

“The divine Marat, with one hand hanging over the edge of the bath, limply holding its last pen, and his breast transfixed with the sacrilegious wound, has just breathed his last. On a green desk placed in front of him his other hand is still holding the treacherous letter: ‘Citizen, my extreme misery suffices to give me a right to your benevolence.’ The water in the bathtub is red with blood, the paper is blood-soaked; on the ground lies a great kitchen knife reeking with blood; on a wretched packing-case which comprised the working-furniture of the tireless journalist we read: ‘A Marat, David.’ All these details are as historical and real as a novel by Balzac; the drama is there, alive in all its pitiful horror, and by an uncanny stroke of brilliance, which makes this David’s masterpiece and one of the great treasures of modern art, there is nothing trivial or ignoble about it. The most astonishing thing about this extraordinary poem is the fact that it is extremely rapidly painted, and when you think of the beauty of the design, this becomes quite staggering. It is the bread of the strong and the triumph of the spiritual; as cruel as nature, this picture has all the perfume of the ideal. Where now is that famous ugliness which holy Death has so swiftly wiped away with the tip of his wing? Henceforth Marat can challenge Apollo; Death has kissed him with his loving lips and he is at rest in the peace of his transfiguration. There is something at once both tender and poignant about this work; in the icy air of that room, on those chilly walls, about that cold and funereal bath, hovers a soul. May we have your leave, you politicians of all parties, and you too, wild liberals of 1845, to give way to emotion before David’s masterpiece? This painting was a gift to a weeping country, and there is nothing dangerous about our tears.”

Charles Baudelaire, “The Museum of Classics at the Bazar Bonne-Nouvelle,” Art in Paris 1845-1862. Salons and Other Exhibitions, Jonathan Mayne, trans. and ed. (Oxford: Phaidon, 1965), 34-45.

Similar Subjects by Other Artists:

Léopold Boilly, Triumph of Marat, 1794. drawing (Château de Versailles)

Paul Baudry, The Assassination of Marat, 1860 (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nantes)

Jules-Charles Aviat, The Death of Marat, 1880 (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen)

Lucien-Etienne Melingue, Jean-Paul Marat, 1880 (Musée de la Révolution Française, Vizelle)

Web Resources:

About the Artist

Died: Brussels, 29 December 1825

Nationality: French

Buy the Book

Buy the Book